What happens when the political music stops in Malawi?

Malawians go to the polls on 16 September.

It’s a country in perennial crisis, one made and exploited by its elites. The means to get out of it requires no miracles, but a clear, carefully prioritised strategy and a leadership ruthlessly focused on removing the obstacles to growth and jobs. The only means of changing this pernicious system, which has locked the country in poverty, is through politics.

Malawi’s per capita income is just $550, less than one-third of the sub-Saharan African average. It is less, too, than that of neighbouring Mozambique, despite the slowness of Maputo’s recovery from years of civil conflict. Malawi ranked in the four poorest countries worldwide at independence on 6 July 1964; today it sits at 184th of 188 countries, with only CAR, Yemen, Burundi, Afghanistan and South Sudan below it, all countries beset by civil war.

These concerns are felt by the Malawian people. A recent poll conducted by SABI Strategy identifies the principal concerns of the population as the cost of living and poor support for farmers. This makes the forthcoming 2025 election all the more important in terms of the policy plans of the various political parties and the integrity of the process itself.

The September election is the first since the highly contested June 2020 event. This election had followed the annulment of the results of the May 2019 presidential elections, in which the incumbent, President Peter Mutharika of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), was re-elected with 39% of the vote, defeating Lazarus Chakwera of the Malawi Congress Party (35%) and Saulos Chilima of the United Transformation Movement (20%). However, the presidential election was challenged in court by Chakwera and Chilima as a result of the so-called ‘Tippex’ scandal. In February 2020 the Constitutional Court annulled the presidential election results and ordered fresh elections to be held.

According to the abovementioned polling research, the 2025 election threatens to undo the grip of the ruling MCP, not least given the impact of several other smaller parties, including the People’s Party led by the 74-year-old Joyce Banda and the United Democratic Front of former cabinet minister Atupele Muluzi. Chilima’s UTM is now represented by Dr Dalitso Kabambe, after its previous leader, the former vice-president, died in an air crash in June last year after he had fallen out with his boss over corruption allegations.

The key question is less about the September election, however, than which political factions will form an alliance after the first round, given that currently no party looks set to win outright in the first round with the required 50%+1.

This also serves to make the election one of the most contested on policy matters, given slow economic growth against a booming population (which has increased from 11 million in 2000 to over 21 million today) and the cut-back in aid which, together with low growth, has left the government with a budget deficit forecast as high as ten percent this year in a thin $11 billion economy.

With an estimated 300,000 civil servants, including some 1,000 in State House, and an apparently insatiable appetite for top-of-the-range VX Land-Cruisers, 90% of the budget is consumed by salaries, pensions and interest on debt. For some the music is still playing loudly, despite the shortages of fuel and rising inflation.

Real GDP growth slowed to an estimated 1.8% in 2024, partly due to drought affecting agricultural production. The World Bank indicates a growth rate of just one percent for 2025, down from earlier projections of 4.8%. Against the population growth rate of 2.6%, this translates to a contraction in per capita GDP. The current account deficit reached 18.7% of GDP in 2024. With the cutback in US aid spending, there is now a $2 billion hole in forex needs with just $1 billion in annual earnings. Little wonder the blackmarket exchange rate is at 4,400 Kwacha to the US$ (and climbing) compared to the official, pegged rate of 1,734.

Malawi’s debt levels are precariously high, with public debt projected at 86% of GDP in 2024, and continuing to climb. With poverty affecting an almost unbelievable 70% of the population, high levels of food insecurity are the norm, one of the ‘push’ factors behind rapid urbanisation, which has grown from under 5% at independence to 20% today and is projected to grow to one-third of the estimated 40 million strong population by 2050. This excludes the estimated three million Malawians who have left for greener pastures in South Africa’s cities.

These issues appear clearly as priorities for the population in the above-mentioned poll, which found inter alia:

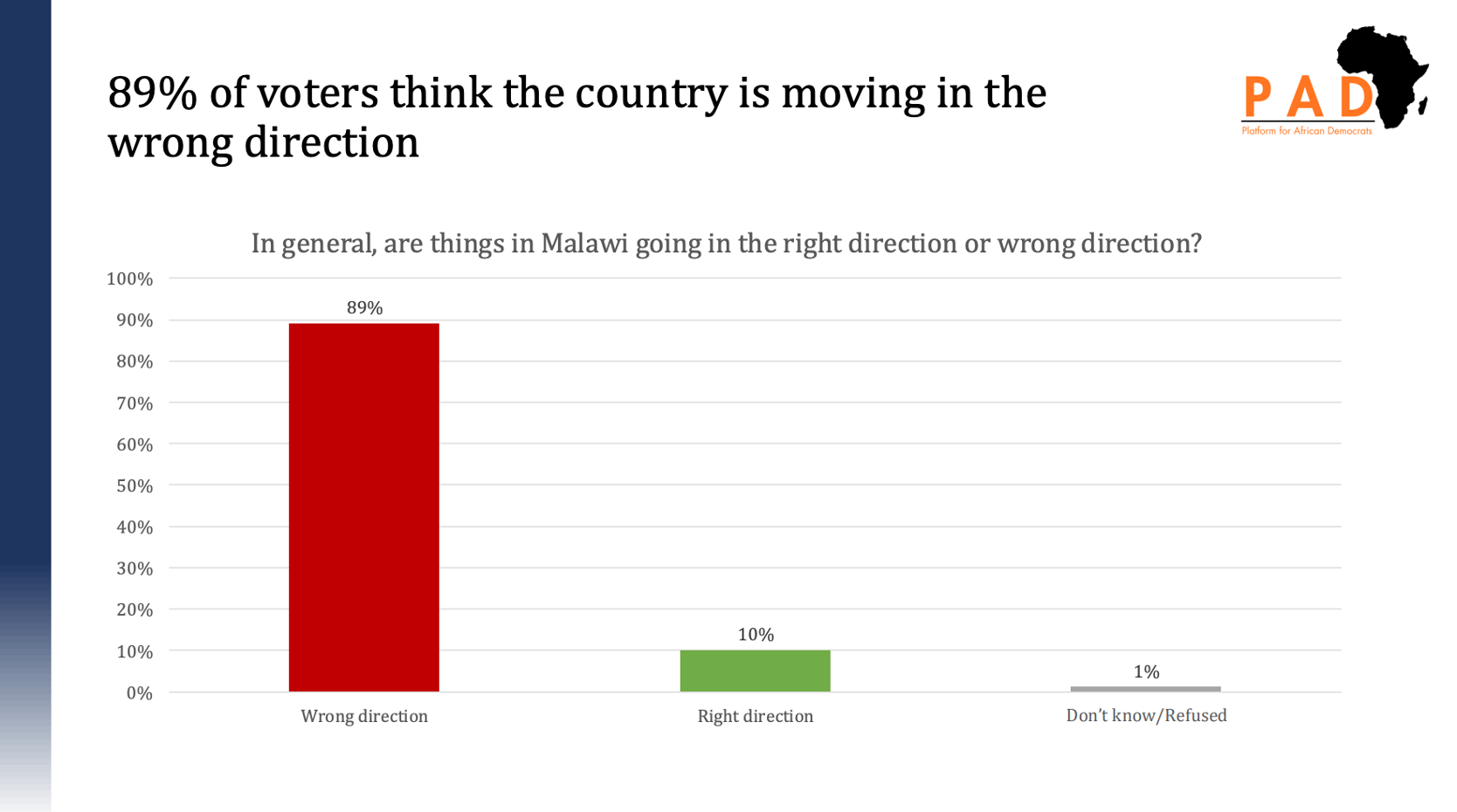

Over 89% of voters believe the country is moving in the wrong direction.

The majority of Malawians cite the cost of living as the biggest issue facing the country. ‘Support for farming’ is the next biggest issue.

71% of respondents surveyed indicate that life for them and their families has got worse in the past five years. This is largely due to economic factors.

Malawi is no exception to the problem of a ‘rentier’ political economy, where the focus for the elite is on extracting income from rents, usually from foreign entities, rather than developing through improving productive capacity and competitiveness.

As the World Bank described it in a 2018 study, “Malawi’s stagnation is in large part driven by a stable but low-level equilibrium, in which a small group of elites compete for power and political survival through rent seeking. The competitive-clientelist political settlement creates strong incentives for policies that can be seen to address short-term popular needs (such as agriculture subsidies, market and price distortions), while undermining the ability to credibly commit to fiscal discipline and long-term reforms needed to spur productive structural transformation.”

Essentially the elite shapes policy choices and practices in a manner that enriches them before all others. In Malawi, this takes the form of state intermediation in agriculture pricing while preventing exports, ensuring the price to the farmer is low. In one of the most egregious forms of exploitation, the produce is stored and then sold back to the farmer at a higher price later in the season when hunger bites.

The list is endless. The engineered failure of railways to drive road transport monopolies to fuel importers benefiting from the collapse of power grids to the political engineering around both the volume and the distribution of aid, especially emergency humanitarian assistance, to transit charges and systems of fuel and agriculture subsidies.

But the music is faltering even for the select few in Malawi as the population increases. As a consequence of the low export levels (and corresponding forex shortage), the country has experienced fuel shortages, further worsening economic activity. Infrastructure development is lagging, and the country faces challenges in developing human capital.

Overall, Malawi’s economic situation is fragile, with a need for both short-term stabilisation measures and long-term structural reforms to address the underlying challenges. The current government’s attempts at reform can best be summarised by the appointment of a presidential economic advisory board only three months before the election, a clear case of better never than late.

As the World Bank notes in its most recent report (in 2023) on Malawi, Narrow Path to Prosperity, the country’s disappointing growth record “can be attributed to policy choices that have worsened an already unfavourable external environment and resulted in significant fiscal and external imbalances”. To this can be added policies which “over many decades have aimed to promote food self-sufficiency rather than commercial farming, leaving most Malawians in an underperforming agricultural sector”.

The report goes on to say that, in Malawi, “both grand and petty corruption is widespread” while “(r)eforms at the turn of the century had little effect on underlying systems.” Rather, “(i)nefficient types of corruption often result from a political settlement characterized by short-horizon decentralized rent-seeking. The most effective path to power, which is concentrated in a strong presidency, is co-opting elites that represent competing factions organized by identity, such as ethnicity and religion, rather than ideology. Factions centred on a big man or woman from a small ‘bwana class’ impervious to formal institutional change find that the way to power is paying rents to maintain their deals-based support.”

The Bank also found that “[S]tate resources often do not translate into developmental gains due to insufficient government effectiveness. This is in part because presenting the impression of commitment, coordination, and cooperation, rather than its reality, is strongly incentivized. Prima facie evidence of this is the large number of high-quality planning documents that Malawian government institutions produce.”

Basically, like Malawians, outsiders may have simply contributed to the rent-seeking by offering a pretence of change and form of diplomatic protection.

Perhaps the most interesting question of all is why Malawians remain apathetic in the face of such obviously weak or indifferent leadership. This is down to what the political scientist Chikondi Chidzanja says is a combination of factors, including the “bystander effect”, where “individuals fail to act because they assume someone else will”, a condition shaped by systemic government failures along with historical, political, and cultural dynamics. Such apathy and learned helplessness reflect repeated reform failures, frequent government governance collapses (such as over passports and fertiliser distribution at different ends of the socio-economic spectrum) and deeply entrenched corruption.

This goes hand-in-hand with tribalism and patronage which ensures disunity, and a related degree of media corruption and complicity, blurring accountability. Democracy is, in this environment, increasingly seen as a disconnected theatre, ritualistic rather than participatory. The result is that citizens disengage and fail to demand change. Failure, he says, is normalised.

‘Why will it be different this time?’ should thus be a question on the lips of all Malawians. The answer lies in leadership and whether it can use its agency and mandate to break the perverse political economy which has plagued the country since independence. For the most part, however, the contenders represent the status quo and a generation which has been hands-on (and sometimes -in) in the creation of this political economy. But this music is about to stop in the face of an economic meltdown, which coincides with the most important election since the advent of democracy in 1964.

The answer as to how Malawi emerges depends on who selects that leadership, however, and whether it votes on the issues or the tribal and religious make-up shaping political choices. Identity over issue is the first refuge of the scoundrel politician.

The key actions to get the economy stabilised and moving in the right direction again hinge on floating the Kwacha, driving austerity in government, and opening up to markets, including ending export bans, which only punish the poor farmer. But these economic actions are profoundly political.

“It’s the economy, stupid!” was the defining message in the 1992 US presidential campaign, won by Bill Clinton from the incumbent George HW Bush. It put its finger on the economic trend in determining whether voters were satisfied or whether they would vote a government out.

“It’s the politics, stupid” should be the mantra for anyone engaging in reform with Africa. As Malawi’s performance reminds, you cannot disconnect economic performance from political outcomes.